Growing up in east London, Yennaris had perhaps the most British of boyhood dreams: he wanted to become a famous soccer star. Born in David Beckham’s stomping ground of Leytonstone to a Cypriot father and a Chinese mother, Yennaris got off to a good start.

Aged 7, he joined the Arsenal FC Youth Academy, a production line for Premier League talent, and went on to play for the England national side at youth level. But after a series of injuries cost him a prestigious scholarship, relegating him to the lower league dressing rooms, Yennaris opted for another route to stardom.

He looked to China.

Earlier this year, Yennaris signed with Beijing Sinobo Guoan FC, a club that is now worth morethan Italy’s AC Milan. Within months, he became the first naturalized player to score in the Chinese Super League (CSL) and to play for China’s national side, in a game against the Philippines.

Yennaris is not alone. In January, John Hou Saeter, who also has a Chinese mother, renounced his Norwegian passport to become Chinese and join Beijing Guoan. And they could soon be joined by other foreign-born players who can’t even claim partial Chinese ancestry. Two Brazilians and one Portuguese transfers are tipped to join the Chinese national squad in time for the Qatar 2022 World Cup. Players who are not ethnically Chinese can play for the Chinese side under FIFA eligibility rules after five years of residency in that country.

Their decision says as much about the rising power of a Chinese passport as it does about the nation’s monied sporting landscape. Perhaps more importantly, though, for a country in the grip of a Han nationalist movement, it also raises important questions around identity.

“China has such a black and white definition of what’s Chinese and what is not,” says Cameron Wilson, a Chinese football writer in Shanghai. “This actually challenges the notion of what being Chinese is in a very public way.”

The first Swedish footballer in China

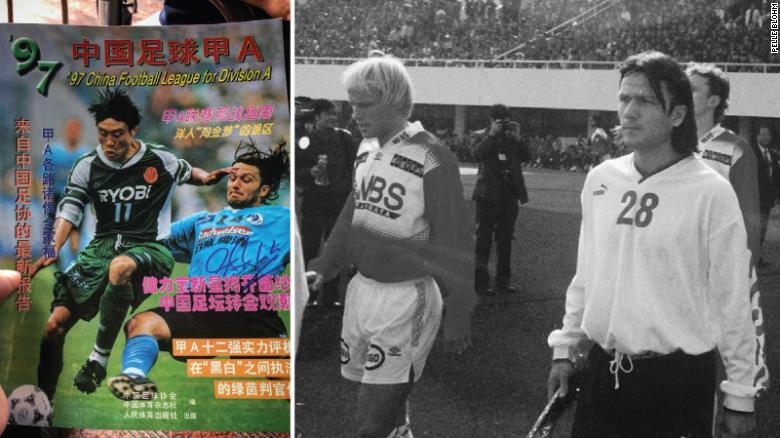

When Swedish midfielder Pelle Blohm arrived in northeast China to play for Dalian Wanda (now Shide) in 1995, the city was gripped by sub-freezing temperatures. “The Siberian wind was coming in from the bay. It was a winter but without snow,” remembers Blohm. “It was not pleasant.”

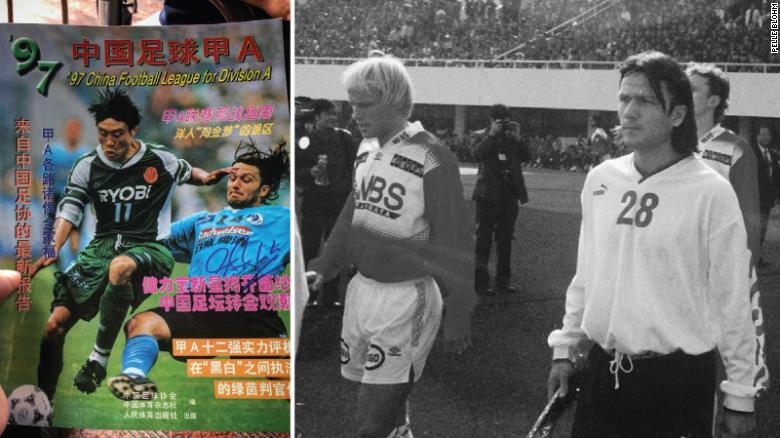

In the 1990s, the Swedish game was full of part-time professionals, the pay was bad and Blohm says he was yearning for adventure. Professional football was only in its third year in China when Blohm began playing in the Jia-A season — China’s equivalent of the Premier League, which became the CSL in 2004 — but Blohm says the stadiums often attracted 35,000 fans, although that was short of their 55,000 capacity.

The level of professionalism, however, was lacking.

“The players were smoking and drinking a lot … the football field was quite bad and there was never a dressing room. We had to get ready in the hotel,” says Blohm, who was immediately asked to cut his long hair short, to conform with the league’s strict appearance code. The Swede politely refused.

The club didn’t employ an interpreter for two months, and before then “nobody spoke in English or any other language except Chinese, as I can remember,” he adds. Blohm, who was the first Swedish professional soccer star to play in China, was paid in US dollar bills, but for months couldn’t find a bank account that would even take his foreign currency.

In the mid-1990s, most Chinese hadn’t been abroad. And those who did travel went on group tours run by government-approved operators. Often, travelers had to wait around six months for a passport, says Wolfgang Georg Arlt, who ran a Beijing-based company organizing Chinese tours to Germany throughout the 1990s.

“And at that time it was not really passport, it was a piece of cardboard called an exit visa,” he says. Couples were not often allowed to travel together — “it was either the husband or the wife who could travel. The other was staying behind as a hostage,” Arlt adds.

Rattled by the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union in 1991, China was worried that once holidaymakers saw what was beyond their border, they wouldn’t want to come home, he says.