Robert Rubin famously launched a “strong dollar policy” for the US in the 1990s, helping to establish a narrative of American economic strength for the latter half of that decade. Chinese President Xi Jinping is now taking a page out of the former Treasury secretary’s playbook.

It’s essentially a 180-degree turn from the direction Beijing was headed in for close to a generation. Starting in the mid-1990s, China spent a decade regularly intervening in the foreign-exchange market to keep the yuan at a pegged rate to the dollar. Policymakers were essentially maintaining an undervalued exchange rate to help exporters and further the process of industrialization.

By 2019, when then-US President Donald Trump declared China an official manipulator of its exchange rate, Beijing had largely stepped away from that approach. By then Chinese producers were well embedded in the global supply chain. Even Trump’s trade tariffs didn’t do much—Chinese producers simply re-routed a share of their shipments.

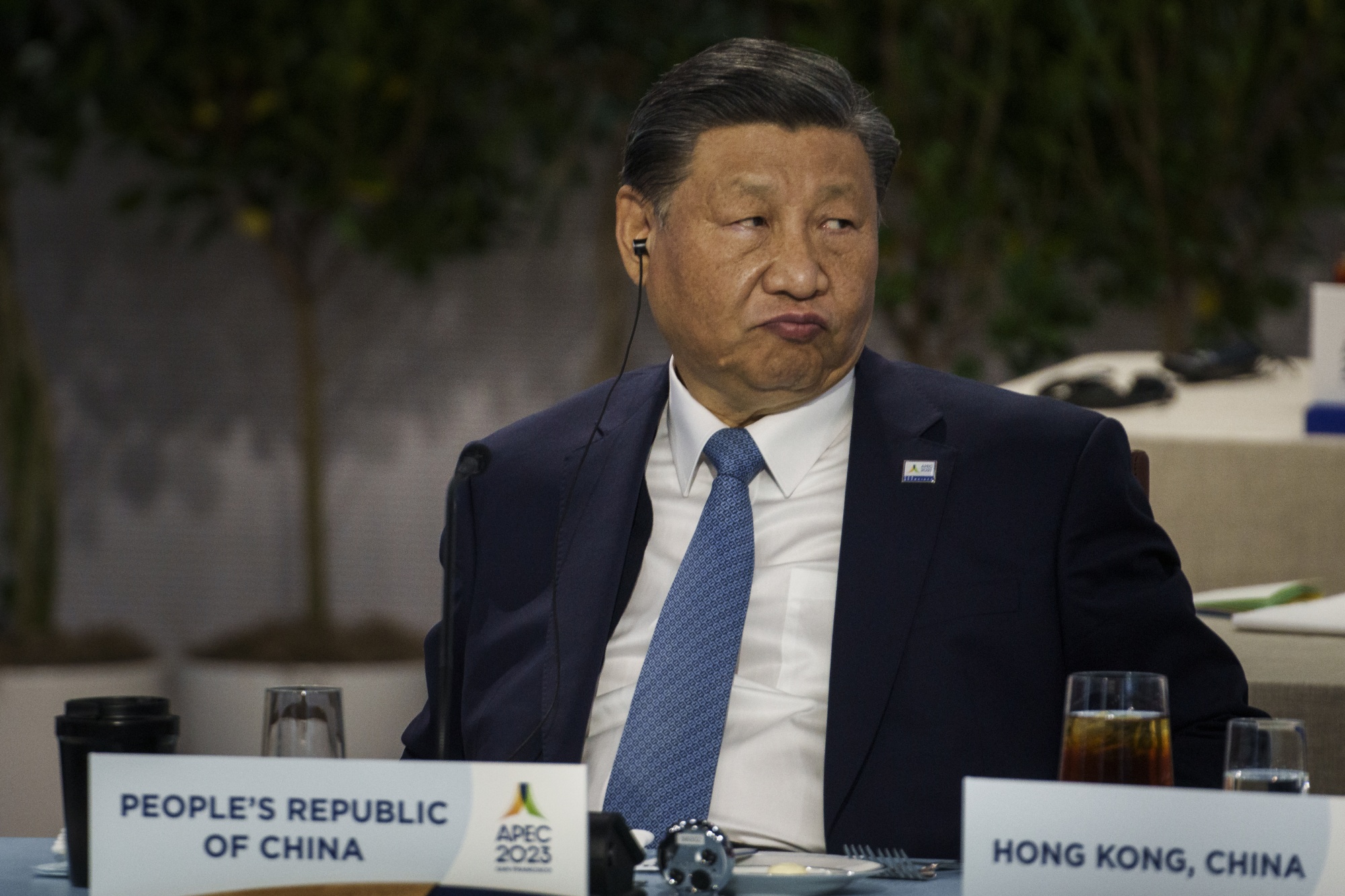

What Xi wants now is to establish China—as he said in his state-of-the-union equivalent last month—as a global “financial power.” For that to happen, it would help if the world viewed the yuan as a stable or appreciating asset, one that can serve as a reserve-currency anchor. Indeed, Xi listed “a strong currency” as the first of several key elements for achieving his goal.

While a strong yuan policy may also have some negative side effects for China’s economy, it’s something fans of the dollar should take note of.

Robert RubinPhotographer: David Paul Morris

In recent years, China’s preference for a strong yuan has been made apparent, particularly when the currency showed strong depreciation tendencies. The yuan has been under pressure (as have many currencies) thanks to the US Federal Reserve’s monetary tightening campaign, as well as concerns of a downshift in Chinese growth and trouble in its financial system.

Last year, Beijing kept up a steady defense of the yuan through a raft of technical measures, including setting the daily official reference rate at a stronger level than traders expected. The central bank sometimes highlighted its determination to correct “one-way bets” in the exchange markets.

By November, the maneuvers reached a level unseen in well over a decade, according to Bloomberg’s analysis. On one occasion in December, officials sought to support the yuan after Moody’s Investors Service cut China’s credit outlook.

While a cheaper yuan makes Chinese exports even more competitive, the worry is that it also feeds a “sell China” narrative—discouraging global investors from putting money into the country. Headlines on the yuan sliding to its weakest level since before the global financial crisis aren’t exactly conducive to foreigners deploying capital into the country.

Xi Jinping Now Says a Strong Currency Is in China’s Interest

The yuan is weaker now than it was a decade ago

Similarly, there was something of a “sell USA” sentiment back in the mid-1990s before America’s adoption of strong-dollar rhetoric (stocks and bonds had down years in 1994). Rubin’s new mantra wasn’t so much a detailed set of policy measures—although the US did on occasion intervene in markets—as it was a positive narrative of American economic strength.

Xi has now put China’s entire political structure on notice that making his nation a major financial power is a major priority. In a Jan. 16 address to leading cadres around the nation and attended by the top Communist Party leadership committee (save Premier Li Qiang who was in Davos), he surprised observers by focusing on China’s financial system.

It was the first time in more than two decades that this annual speech by a Chinese leader addressed finance. The last time was 1999, in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis.

Now, “the financial system is all the rage in policy circles,” China analysts at the consultancy Trivium wrote in a note this week. The Chinese Communist Party’s top theorist, Qu Qingshan, declared in an opinion piece published Wednesday that “only by accelerating the construction of our financial power and continuously improving our country’s competitiveness and voice in international finance can we seize the initiative in the game of great powers,” Trivium said.

Xi JinpingPhotographer: Philip Pacheco/Bloomberg

Pursuing a strong-yuan policy may also bring undesired consequences for China. Notably, said Rory Green, chief China economist at TS Lombard, it “could act to constrain monetary policy.” He explains that the People’s Bank of China may be wary of easing monetary policy because doing so would create downward pressure on the exchange rate.

“Needless to say, an artificially strong currency attached to a weak economy is not a good combination,” Green wrote in a note Thursday.

But a focus on protecting the yuan’s value could encourage the growth of offshore financial markets denominated in China’s currency, which are now just in their infancy. Singapore’s state-owned investment giant Temasek just this week unveiled plans for its debut offshore yuan bond. And one of South Korea’s biggest debt issuers, Korea Development Bank, said it was mulling expanding funding in that denomination.

For those worried about downgrading of the dollar in the global financial system, Xi’s strong-yuan policy bears close watching.